Paintings/Sculptures

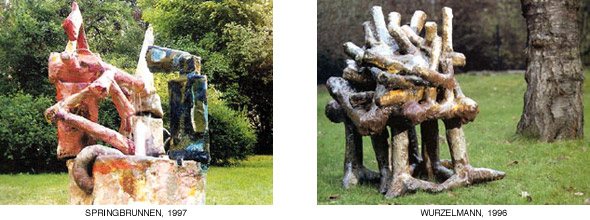

“But Paradise is barred, and the cherup is is behind us; we must undertaken a journey around the world to see if somewhere, perhaps on the far side, it is still open.” – Heinrich von Kleist On the Puppet-Theatre Wurzelmann 1996

Sebastian Heiner is one of those by now rare artists of his gerneration who work on the by-ways of the contemporary art world. With no regard for avangardist tendencies and mordernistic trends, he continues untroubled along the tradotional path: painting on canvas. Initially, this may appear old-fashioned, unspectacular for a young artist – but spectacular worlds are in fact revealed to those viewers who permit themselves to be seduced by Heiner´s pictures. They leave the door open to the imagination in manifold ways, and not only to the imagination of the artist, bur also – and primarily – to that of the viewer. The range of moods and associations to which the pictures give birth is as diverse in character as the receivers themeselves are different. The viewer therefore always takes an active role, his perception is challenged and the open work of art – in these sense proclaimed by Eco – is only completed by his own ideas. The poetic compositions by this artist, who was born in 1969, lead the viewer into dream worlds and abstract and inhospitable realms which are like a projecton surface for the familiar and the well-known: soulscapes of burning into passion in which one finds oneself again, just as one can hear the jangling of their crisp, sharpe coldness.

The themes develop from the powerfulness of the colour, and from the colour symolism which Heiner employs for his works, intensifying it into a personal symbolism with his amorphous, abstract froms. Heiner tells of love and loneliness, of pain and consolation, of discord and reconcilation and of man´s constant strugggle with himself and with superior powers – with the power of Nature, faith and society. The images become transmission belts of existential questions regarding human existence, permitting the encounter between viewer and picture to develop into productive reflection and communication. On a thin line between art informel and figuration, the vitality of Heiner´s works stems from their expressive impetus, from the combination of colour and a dynamic ductus, the forms spontaneously put to canvas. The pastose application of paint, increased to produce an almost relief-like character, makes it seem as if the artist is simultaneously bringing the synamism of the image to a halt. The extreme friction and tension which Heiner creates with this counterplay and interplay of light, dynamic brushstrokes and centimetre-thick layers of paint, applied with a palette knife, is in contrast to a generally uniform choce of colours, then examining the psycho-physical effect of this in numerous variations. He entices from it a range of tones from warm and glowing to hotly burning, as in by using a soft red verging on a pastel tone.

The polarity betwen pulsating vitality and endless isolation in «City without Balance» reflects the vital consciousness of the big city dweller in a very concrete way: at imes, an immensely lively dynamism reigns, but by contrast a great loneliness then extends over wide areas with clear contours. The noise of the big city is audible to us in sparks of black and white evoked by the sensitive bruschstrokes in th left-hand, lower part of the picture. Many levels of steel and concrete constructions are overlapped like bridges. Their paths are repeatedly cut off, leading to nothing or into dark chasms. They dissolve into curves whose speed appears to throw us off the track. The Dadaist Richard Huelsenbeck wrote in the early twenties: it does not draw into itself like Paris, it doesn´t mail you fast like Moscow, it doesn´t comsume you like New York or Shanghai. Berlin is a movement without a centre: In «City without Balance», the centre also moves into ever new places: as a result of the nuances of colour and the mode of application, everchanging centres to the image spring to the fore. And whilst Huelsenbeck concludes: that is why one soon becomes a trifle crazy in Berlin, Sebastian Heiner opposes the madness a little with this picture, as with his work in general; for as apocalyptically as the deserted, chasm-like streets fall in upon each other, as cold as the pastos, white sky may appear: from the right-hand edge of the picture, a mass of colour intrudes into the events like a warm weather front: a range of mountains in bright red and orange tones. It is true that here too, peace only partially reigns – in the broken, soft, light red and violet tones – washed layers and flowing forms struggle against thrusts of the brush recalling flashes of lightning. But the struggle is a struggle of life, a dance of warmth and love whose erotic spark ahs already leapt into the realm of darkness. Whether the sketchy figures in «Departure II» have just escaped from this realm of darkness or are wandering blindly into the maw of hell remains open to the viewer´s interpretation. Like astral bodies, the figures appear at home between the worlds. At first, the faceless and nameless mass ahs the effect of an accumulation of anonymity, but these figures also touch the individual, like an awakening from a disturbing dream.

They approach each other, touch each other and lose themselves, they melt into each other in order to disintegrate at the centre of the picture. The vertical arrangement of the solemn bodies reflects their closeness to the cosmos and their simultaneous affinity with the earth, ancient stories and biblical myths: the dominant red and thr rain of fire in the left half of the picture point to the story of Moses and the Old Testament plagues which initated the Israelite´s mover from Egypt, one again reflected in th situation of departure. The artist makes the figures step out of the picture as if in a relief, and his pastos ductus and the structually determined employment of piant emphasise a spatial aspect in which the compositon and the idea pont far beyond the limitations of the canvas, inviting the viewer himself to depart – to take a Journey around the World. At the same time, this picture can be read as a present-day statement on the situation of Berlin; the city in which Heiner was born and grew up, to location and object of his studies, the place where he lives and works, and a city which, like no other in the 90s, is in a state of permanent departure. With its surreal narrative form, the picture appears to caution us against a new Babylon. But Heiner´s wish is certainly not to propose theses or to proffer supposed answers; in an unobtrusive and pleasantly irritating way, he makes us aware of the question as to where the departure and our own self-assurance will lead to.

The red pictures are contrasted by a series of variations in blue; here too, Heiner succeeds in heightening the use of colour and form to create his own metaphors. In the picture «Falling Night», the extreme overlapping of the blue violet tones with black structures evokes an ambivalent, paradoxical situation of security within an apocalypse. In a nightmare fashion, people, crosses and ruins fall upon a fragment of world whose composition and colourfulness almost appear romantic. The last trumpet of the last judgment sounds out into the wistful, lost blue. The visionary aspect of the Revelation of John, redemption, forces its way into the foreground like a glimmer of hope in a broad front of violet – the holy colour – between romantic longing, the world and the end of the world.

Springbrunnen 1997

Pictures like «Falling Night» which draw the viewer into them with their agitation and stirring staccato are in contrast to contemplative works like «Water» for example; its broad, quiet areas of colour radiate a meditative calm. Like a mild summer mist, the lyrical cyan blue spreads across an imaginary landscape whose transfigured appears both close enough to grasp and infinitely far away. The application of colour, appearing almost like a glaze, lends great transparency to the composition. The viewpoint breaks the surface of the water and penetrates just below in into depths where the viewer may drive as if into a warm sea.

In the plastic work which he has pursued parallel to painting for three years, as if in a dialogue with the images, Heiner transforms the mobile, moving aspects of his images into the third dimension. In the sculpture, the spiritual and epic moment of the pictures receives the corporeality already resonating in the painterly gestures. In some of the pictures one almost believes it is still possoble to sense the movement of the artist, his physical work on the canvas whilst viewing them. The step to sculpture in Heiner´s case therefore appears immanent and logical in his work: for sculpture is surely an expression of corporeality, and thus implies a greater proximity to man, who has always been – directly or indirectly – a theme in Heiners works. The rough structure of the material used for the sculptures, which is prepared from wastepaper and glue, corresponds to the relief-like texture of the pictures. It is not only the fragmentary forms of the sculptures which expresses great vulnerability by means of materiality. When Heiner works with polyester, he also retains the rough structual aspect of the material rather than giving it a highly polished, smooth surface. The mythical creatures, to which Heiner gives titels like «Sunman», «Rootman» or «Lady Rainblue», appear to be a synthesis of the human and the four elements. In the sculptures, the metaphysical character of the pictures receives a new sensuality when these beings steps out, as it were, from the canvas and take on tangible, plastic shape. The ethereal forms and figures appear to be firmly rooted in the earth, occasionally they even take on the gnarled form of gnome-like, underground beings. The exiting moment of the vertical sculptures lies precisely in the relation between this rootedness in the soil and a simultaneous emphasis placed upon the opposite direction. Their oversized hands reach up into the air, into sky, to all fourr points of the compass, and one feels tempted to touch and to stroke these mythical beings. As a result of their imploring manner of ‘reaching out into the world’, one would like to offer consolation to some. But the sculptures throw back this feeling like a long shadow – proudly, calmy and insistently questioning who precisely needs a consoling hand in this encounter.

Michaela Nolte

Berlin 1998

“Doch das Paradies ist verriegelt und der Cherub hinter uns; wir müssen die Reise um die Welt machen, und sehen, ob es vielleicht von hinten irgendwo wieder offen ist.” – Heinrich von Kleist, “Über das Marionettentheater” – Wurzelmann 1996

Sebastian Heiner gehört zu den rar gewordenen Künstlern seiner Generation, die sich auf den Nebenwegen der zeitgenössischen Kunstmaschinerie, abseits avantgardistischer Tendenzen und modernistischer Kunstströmungen, unbeirrt auf dem traditionellen Hauptweg bewegen: der Malerei mit Leinwand und Farbe. Das erscheint für einen jungen Künstler zunächst unzeitgemäß, unspektakulär – doch denjenigen Betrachtern, die sich von Heiners Bildern verführen lassen, eröffnen sich durchaus spektakuläre Welten. Auf vielschichtige Weise öffnen sie der Phantasie, nicht nur der des Künstlers sondern auch und zuförderst der des Betrachters, Tür und Tor und die Palette der Stimmungen und Assoziationen, welche die Bilder aufwerfen und freisetzen, sind immer so weitgefächert, wie ihre Rezipienten unterschiedlich sind. So wird der Betrachter immer auch zum aktiven Part, dessen Wahrnehmung gefordert ist und der das offene Kunstwerk – im Sinne Ecos – mit seinen eigenen Gedanken erst vollendet. Die poetischen Kompositionen des 1964 geborenen Künstlers führen den Betrachter in Traumwelten und Gefilde, die in ihrer Abstraktion und Unwirtlichkeit gleichsam eine Projektionsfläche für Bekanntes und Vertrautes bieten: Seelenlandschaften, in deren glühender Leidenschaft man sich ebenso wiederfindet, wie man ihre scharfe Kälte klirren hören kann.

Die Themen entfalten sich aus der Kraft der Farbe und aus der Farbsymbolik, die Heiner für seine Arbeiten nutzt und mit seinen amorphen und abstrakten Formen zu einer eigenen Symbolik verdichtet. Heiner erzählt von Liebe und Einsamkeit, von Schmerz und Trost, von Zwist und Versöhnung und vom steten Kampf des Menschen mit sich selbst und mit den übergeordneten Mächten – mit der Kraft der Natur, mit dem Glauben und mit gesellschaftlichen Kräften. Die Bilder werden zu Tansmissionsriemen existenzieller Fragen menschlichen Seins und lassen die Begegnung zwischen Betrachter und Gemälde zur fruchtbaren Reflexion und Kommunikation werden. Auf einer Gratwanderung zwischen Informel und Figuration leben Heiners Arbeiten vom expressiven Impetus, vom Zusammenwirken der Farbe und dem dynamischen Duktus, mit den spontan auf die Leinwand gebrachten Formen. Im pastosen, bis zu Reliefcharakter gesteigerten Farbauftrag scheint der Künstler der Dynamik gleichsam wieder Einhalt zu gebieten. Der extremen Reibung und Spannung, die Heiner mit diesem Gegen- und Ineinanderspielen von leichten, dynamischen Pinselstrichen bis zu zentimeterdick gespachtelten Farbschichten erzeugt, steht eine zumeist einheitliche Farbwahl gegenüber. Ausgehend von einer dominierenden Farbe, bricht er ihre Qualitäten, indem er sie aufhellt oder abdunkelt, setzt ihr unbuntes Schwarz oder Weiß entgegen, was den Charakter, zu Beispiel des Zinnoberrots in “Erregter Zustand”, in bizarrer Weise steigert. Rot, der aktivsten aller Farben, verleiht er durch seinen heftigen Gestus einen intensivern Charakter, dessen jeweilige psychophysische Wirkung Heiner in vielfältigen Variationen unersucht. Er entlockt ihr warm leuchtende bis heiß glühende Klänge, wie in “Aufbruch II” oder “Erregter Zustand”. Dann wiederum verleiht er Bildern wie “Reigen” oder “Begegnung”, mit einem zarten, ins Pastell übergehenden Rot eine stille Melancholie.

Die Polarität von pulsierender Lebendigkeit und grenzloser Vereinzelung in “Stadt ohne Gleichgewicht” spiegelt sehr konkret das Lebensgefühl des Großstadtmenschen: mal herrscht eine ungemein lebendige Dynamik, dann erstreckt sich dagegen eine große Einsamkeit über weite, klar konturierte Flächen. Aus der feinnervigen Pinselführung im linken, unteren Bildteil tönt uns der Großstadtlärm in schwarzen und weißen Funken hörbar entgegen. Wie Brücken lagern vielschichtige Stahl- und Betonkonstruktionen übereinander. Ihre Wege brechen immer wieder ab, führen ins Nichts oder in dunkle Schluchten. Sie lösen sich in Kurven auf, deren Tempo einen aus der Bahn zu schleudern scheint. Der Dadaist Richard Huelsenbeck schrieb zu Beginn der 20er Jahre: Sie zieht dich nicht in sich hinein wie Paris, sie nagelt dich nicht fest wie Moskau, sie frisst dich nicht auf wie New York oder Shanghai. Berlin ist eine Bewegung ohne Mittelpunkt. Das Zentrum bewegt sich auch in “Stadt ohne Gleichgewicht” an immer neue Punkte; mit den Farbnuancen und dem Modus des Auftrags springen stets wechselnde Bildzentren in den Vordergrund. Und wenn Huelsenbeck schließt: Deswegen wird man bald irrsinnig in Berlin, so setzt Sebastian Heiner mit diesem Bild, wie überhaupt mit seinem Werk, dem Irrsinn ein wenig entgegen; denn so apokalyptisch die menschenleeren Straßenschluchten ineinanderfallen, so kalt der pastos-weiße Himmel erscheint: vom rechten Bildrand drängt ein Farbmassiv wie eine Gut-Wetter-Front ins Geschehen: ein Gebirge in leuchtenden Rot- und Orangetönen. Zwar herrscht auch hier nur partiell – in den gebrochenen, zarten, hellroten und violetten Farben – Ruhe, kämpfen lavierte Schichten und fließende Formen gegen blitzartige Pinselhiebe. Doch der Kampf ist ein Kampf des Lebens, ein Tanz der Wärme und der Liebe, dessen erotischer Funke bereits ins Reich des Dunkels übergesprungen ist.

Ob die schemenhaften Figuren in “Aufbruch II” diesem Reich des Dunkels gerade entkommen oder aber blindlings in den Schlund der Hölle wandern, bleibt der Lesart des Betrachters überlassen. Astralleibern gleich, scheinen die Figuren zwischen den Welten angesiedelt zu sein.

Die gesichts- und namenlose Masse wirkt zunächst wie eine Akkumulation von Anonymität und dennoch rühren diese Figuren das Individuelle an, wie nach dem Erwachen aus einem verstörenden Traum. Sie gehen aufeinander zu, berühren und verirren sich, verschmelzen miteinander, um sich im Zentrum des Bildes wieder aufzulösen. In der vertikalen Anordnung der gravitätischen Körper, ihrer Nähe zum Kosmos und der gleichzeitigen Erdverbundenheit, spiegeln sich uralte Geschichten und biblische Mythen: Im vorherrschenden Rot und im Feuerregen der linken Bildhälfte, klingt die Geschichte Moses¡ä ebenso an, wie die alttestamentarischen Plagen, die den Auszug der Israeliten aus Ägypten initiierten, der sich in der Situation des Aufbruchs widerspiegelt. Der Maler lässt die Figuren reliefartig aus dem Bild heraustreten und hebt im pastosen Duktus und dem strukturbetonten Umgang mit der Farbe eine räumlichen Aspekt hervor, in welchem Komposition und Idee weit über die Grenzen der Leinwand hinausweisen und den Betrachter zum Aufbruch einladen – und zur Reise um die Welt. Zugleich lässt sich dieses Bild wie eine aktuelle Stellungnahme zur Situation Berlins lesen; der Stadt, in der Heiner geboren wurde und aufgewachsen ist, in der er und die er studiert hat, wo er lebt und arbeitet und die sich wie keine zweite Stadt der 90er Jahre im Stadium eines permanenten Aufbruchs befindet. In seiner surrealen Erzählweise scheint das Bild an ein erneutes Babylon zu gemahnen. Doch liegt es Heiner fern, Thesen aufzustellen oder vermeintliche Antworten zu geben; auf eine unaufdringliche und wohltuend irritierende Weise, rückt er die Frage in Bewusstsein, wohin uns der Aufbruch und unsere Selbstgewissheit führen.

Springbrunnen 1997

Den roten Bildern steht eine Variation in Blau gegenüber; auch hier gelingt Heiner die Verdichtung von Farb- und Formgebung zu einer eigenen Metaphorik. In dem Bild “Stürzende Nacht” evoziert die extreme Überlagerung der blau-violetten Töne mit schwarzen Strukturen eine ambivalente, paradoxe Situation von Geborgenheit in der Apokalypse. Menschen, Kreuze und Trümmer stürzen alptraumhaft auf ein Fragment von Welt, dessen Komposition und Farbigkeit fast romantisch anmuten. In das sehnsuchtsvoll verlorene Blau hinein, erklingt die letzte Trompete des jüngsten Gerichts. Das Visionäre der Offenbarung des Johannes, die Erlösung, schiebt sich im Mittelgrund wie ein Schimmer von Hoffnung, in einer breiten Front aus Violett – der heiligen Farbe – zwischen die romantische Sehnsucht, die Welt und das Weltende.

Bildern, wie “Stürzende Nacht”, deren Aufgewühltheit und ergreifendes Staccato den Betrachter in sich hineinziehen, stehen kontemplative Arbeiten wie zum Beispiel “Wasser” gegenüber, dessen großflächig ruhige Farbgebung eine meditative Ruhe ausstrahlen. Wie ein lauer Sommernebel liegt das lyrische Cyanblau über einer imaginären Landschaft, deren verklärter Horizont greifbar nah und doch unendlich fern zu liegen scheint. Der lasurhaft wirkende Farbauftrag verleiht dem Arrangement eine große Transparenz. Der Blickpunkt bricht die Wasseroberfläche und dringt knapp darunter in ein Tiefe, in die der Betrachter eintauchen kann, wie in ein warmes Meer.

Das Bewegte und Bewegende der Bilder transformiert Heiner in der plastischen Arbeit, die er seit drei Jahren parallel zur Malerei verfolgt, wie in einem Dialog mit den Bildern, in die dritte Dimension. Das geistige und epische Moment des Bildwerks erhält in den Skulpturen die Körperlichkeit, die bereits im malerischen Gestus mitschwingt. In einigen der Bilder glaubt man die Bewegung des Künstlers, seine physische Arbeit an der Leinwand noch beim Betrachten spüren zu können. So scheint der Schritt zur Skulptur bei Heiner werkimmanent und konsequent; ist doch Skulptur Ausdruck von Körperlichkeit und impliziert so eine große Nähe zum Menschen, der in Heiners Werk direkt oder indirekt immer bearbeitet wird. Die grobe Materialstruktur des für die Skulpturen verwandten Stoffes, der mit Makulatur und Leim bearbeitet wird, korrespondiert mit der reliefartigen Textur der Bilder. Nicht nur im fragmentarisch Geformten der Plastiken drückt sich durch Materialität eine große Verletzlichkeit aus. Auch wenn Heiner mit Polyester arbeitet behält er das raue, strukturelle Moment des Werkstoffs bei, anstatt ihm eine hochpolierte und glatte Oberfläche zu geben. Wie eine Synthese des Menschlichen mit den vier Elementen erscheinen die Fabelwesen, denen Heiner Titel wie “Sonnenmann”, ”Wurzelmann“ oder ”Frau Regenblau“ verleiht. Der metaphysische Charakter der Bilder bekommt in den Skulpturen eine neue Sinnlichkeit, wenn die Wesen aus dem Bild quasi heraustreten und eine greifbare, plastische Gestalt annehmen. Die ästhetischen Formen und Figuren scheinen tief in de Erde verwurzelt, nehmen bisweilen selbst die knorrige Form von gnomenhaften Untergrundwesen an. Bei den vertikal ausgerichteten Skulpturen liegt die Spannung gerade in der Verbindung von Bodenständigkeit und einer gleichzeitigen Betonung der Gegenrichtung. Ihre überdimensionierten Hände greifen in die Luft, in den Himmel, in die vier Windrichtungen und man fühlt sich verleitet, die Fabelwesen zu berühren und sie zu streicheln. Manchen möchte man, ob ihres flehenden “In-die-Welt-Greifens”, Trost spenden. Doch werfen die Skulpturen dieses Gefühl wie einen langen Schatten wieder zurück und verharren ruhig und stolz in der Frage, wer in dieser Zusammenkunft der tröstenden Hand bedarf.

Michaela Nolte

Berlin 1998